Learning to Breathe Together

My middle son, Chase, turned 10 this week.

He was born by emergency c-section and when the doctors hooked, reeled, and fished him out he wasn’t breathing.

Hustled like a hot potato to a corner, doctors did what doctors do, and soon his sweet cries filled the operating room which gave Cindy and I permission to exhale and rejoice.

We had a boy. A well-feed 9 pound 4 ounces beautiful, breathing boy.

A boy who walked before he was one.

A boy who could hit a pitched baseball at two (I puffed out my chest a little when I wrote that sentence).

A boy who, on the eve of his fourth birthday, swallowed a lollipop and turned blue and went limp in my arms. Later that day, with my heart still thumping, Chase and I mazed through the aisles of a store when he asked, with his little, fearless blue eyes, “Dad, can I have another lollipop”

And now he’s 10. Stretching into a pre-adolescent alien with braces.

Strong and fast and charged with middle-child enthusiasm– Chase breathes excitement into our family. Into the world. Into me.

It terrifies me to know that my innocent boy will soon be at the mercy of the world and the other night, while sitting on the couch, watching the terrifying news of the day, a thought struck me– my son turns 10 in a year when, on a Minneapolis street, when a single breath started a global revolution.

In a year when the whole world seems to be fighting for air.

My biggest regret as a father is that I can’t play sports with my son.

The black hole in my brain has vacuumed-out most of my athletic neurons.

But Chase is an athlete. Fearless, willed, and eager to defy gravity. Sometimes it’s difficult for me to accept that I can’t play 1-on-1 basketball against him or dare him to hit my fastball. That I can’t, with a sweaty brow, breathe hard with him in the backyard on an soft, summer night.

I never felt more closer to my father than when we played sports together. In the grass, on the blacktop– a fellowship, a chemistry, a shared strand of DNA. Skin on skin. Muscle moving atop of muscle. Our lungs working in and out together– like they should. Leaning on each other. Breathing together. Two things the world, and all it’s colors, needs to do right now.

One of the reasons (besides fame and fortune) why I often write about my children is that writing these stories is my way of lacing my high-tops or sliding on the old baseball mitt. It’s my way to bump into them. To feel them.

Stories, with all their alchemy, allow us to recognize each other. To connect to each other. To breath together in times when air is hard to find.

This week I wanted to share with you two Chase stories. I wrote them both a few years ago. Both take place on our couch. A father staring with amazement at his son. A son, unknowingly, breathing life into his father

I hope you enjoy.

Be well,

Jay

When your Child Learns the “F” Word

(published October, 2016)

I wasn’t ready for it. Not yet.

I mean, I knew it would come one day like a thunderstorm or like something I sent away for in the mail.

But I just didn’t think it would happen on a nondescript morning like this.

But parenthood is funny like that.

One moment you’re cruising along, one hand on the wheel, window down, sunglasses on and then, like a sucker punch, you’re reminded that you’re not in control, and probably never have been. So with a pair of mangled sunglasses dangling off an ear, you straighten up and attempt to piece together what just happened.

Sunday morning.

I wake the coffee maker, and the laptop, move to the kitchen sink and watch slivers of morning light break the dark veil of day and think about you. I think about what I want to say to you this week.

For the past three weeks I wrote about my son Chase, choking in my arms. Over that time, through the vehicles of imagination and memory, I’ve been traversing into the heart of my most unnerving experience.

Frankly, I needed a break.

I wanted to lighten the mood around here. And plus, with this Killer Clown Craze and the Presidential Election ( two unrelated yet often confused headlines) dominating our nightly news, we could use it.

The coffee maker burps, grunts and beeps. I pour a cup and move to the living room.

I park myself on the couch, sip, stare into the glowing face of the laptop and wait. I wait for the barrel-chested ghost of Ernest Hemingway to appear and inspire me, remind me that all I have to do is “write one true sentence” but instead of Ernie H., Chase turns the corner sporting glassy eyes, a spiky tuft of bedhead and his faded green Ninja Turtle pajamas. Pajamas that have been machine-washed too many times. Pajamas that fit him nicely in June but are now thread-stretched to its limits, forcing the brave Donatello to beg for mercy.

Chase curls next to me. He rests his head on my shoulder.

The TV is off yet we watch it like its on. The sun is rising behind me, filling the windows, warming my back.

“Hey dad, do I have a soccer game today?”

“Yes you do buddy.”

“Hey dad, do you think when I’m older I could be a soccer player? Like the kind that plays on TV.”

I tussled his bedhead. Smile and in a hearty dad voice offer my son the most unoriginal dad response I could, “Son, you can be anything you want to be.”

Things were perfectly quit between us. Just a father and his son enjoying the company of each other in the slow of a Sunday morning.

“Hey dad?”

“Yes, buddy?’

Do you know the “f” word?”

Pow! Sucker punch. Chew on that dad.

“Uh, um, uh…yeah? What? I mean, do you?”

“Yeah. Fuck. Fuck is the f-word”

I cocked my head like a little dog when he hears her name and held it for some time just wondering.

“Bud, where did you learn that?”

“School.”

“That’s a bad word. We don’t say that word.”

“Ok Dad I won’t say it.”

But I know he will. I can’t expect him to unlearn the word. I didn’t. You didn’t. The word is now forever buzzing about his brain, like a bee in a jar, waiting for its chance to fly loose and sting his sentences–Fuck me these pajamas are tight!

The sun warmed the windows and my coffee cooled and I held Chase close feeling that weird mix of hilarity and sadness that is parenthood.

Hearing my son, with aggressive bedhead and tight Ninja Turtle pajamas, drop the “f” bomb was– funny. But I understand its significance. It’s gravity and weight. It’s a sad indication that the world has sunk its grimy fangs into him. And there is nothing I can do.

Cindy and I police our language around the kids.

But here’s the scary parental truth– we can only protect, shelter our children for so long. Sooner or later their little bodies will be at the mercy of the world. And yet, as parents we know that we must send our children off into that tumult — to learn, to discover, to get hurt. Like us, they will be damaged and they will return home talking dirty. It’s just the price we all must pay.

So what do we do when our children learn the “f” word?

Cut out their tongues?

Of course not.

We can just reinforce it’s a bad word. And if he says it again I will correct him again.

But I can’t be naive. By identifying words as “bad” I’m only planting seeds of curiosity. Chase will surely lie in bed at night, further stretching out the Turtles, and wonder what other bad words loom out in the darkness, where the killer clowns and presidential candidates reside.

Things were quiet. With Chase’s head still on my shoulder I thought about how growing up, losing innocence, vilifying your vocabulary are as natural and normal as the rising sun.

Hey Dad?

Yeah?

“What do you call a skunk driving a helicopter?”

“What?”

” A smell-a-copter.”

I smiled, tussled his bedhead again and felt the warm reassurance that I still have plenty more quiet mornings with my little boy.

It’s a Wonderful Life

(published November, 2018)

I’m watching It’s a Wonderful Life with my son, Chase, when in between handfuls of popcorn he asks two questions:

- Why did people back then only see in black and white?

- Why did George want to jump off the bridge?

Question one was easy to answer but difficult for my 8 year my son to understand.

I explained that, just like us, people back then saw in color. But this movie was made before color video cameras had been invented, so it could only be filmed in black and white. This caused Chase, a creature of color tvs, color computers, color tablets, color phones to bend his brow and say, “I don’t understand.”

The second question was more difficult to answer, but somehow seemed easier for Chase to understand.

My son didn’t realize that George Bailey stood on the bridge contemplating suicide. George had lost all his money, his business teetered on bankruptcy, there was a warrant for his arrest. Confused and desperate he felt that suicide was the only solution.

Chase has yet to experience the chest-seizing panic that George Bailey felt as he stood on a bridge, looked down at the icy river below, and believed his life was over.

What my 8 year old doesn’t understand is that most adults:

Are terrified of embarrassment.

Fear change.

Define themselves by material possessions and financial success.

Undervalue failure.

Overvalue wealth.

Focus on the wrongs instead of the rights of the world.

Believe they’re not worth saving.

Believe dreaming is childish.

Believe self-pity is acceptable.

Believe running from problems is a formidable solution.

Are so nearsighted they fail to acknowledge all the good they’ve done, the lives they touched, and the people who still need them.

Fail to realize problems catalyze growth and that our problems are not nearly as unique as we think they are and that sometimes shit happens and, if we can sit on the pot long enough, we realize we have the ability and resources to clean it up.

But you can’t say that to 8 year old. You’d give him nightmares.

So I just turn and say, “George wants to jump off the bridge because he’s sad and doesn’t know what else to do. But he’s forgetting about all the friends and family who love him.”

Chase understandingly nods, reaches into the plastic bowl between us, scoops outs a handful of popcorn, looks at me, and flashes a smile that reminds me how wonderful life is.

~~

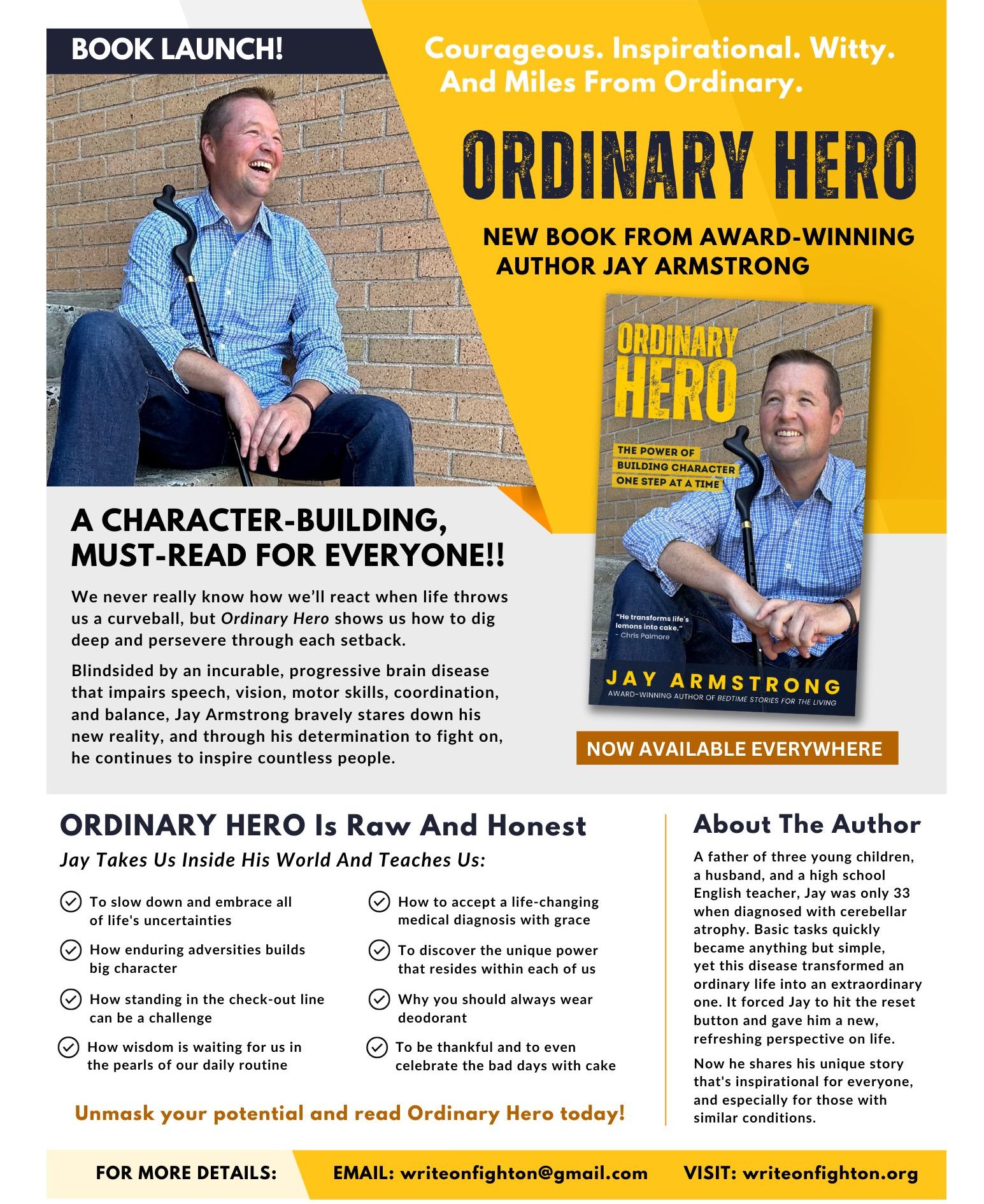

Jay Armstrong is a writer, blogger, speaker, and recipient of the Teacher of the Year award in his school district. Diagnosed with a rare neurological disease that resulted in a hole in his brain– Jay presses on. He hopes to help you find joy, peace, and meaning in life. For Jay, a good day consists of 5 things:

1. Reading

2. Writing

3. Exercising

4. Hearing his children laugh

5. Hugging his wife

(Bonus points for a dinner with his parents and a beer with his friends)