Taking Notes: A Love Story

In a world with Nicholas Sparks it’s hard to write something original about love.

Love is a well-traveled topic. One, I’m sure, you’ve taken plenty of notes on.

Love is patient. Love is kind. Love is engraved your heart and scrolled among the stars.

Love is in air. Love is an open door. And, if you find the right station, love is a battlefield.

Anytime you write about love you ink a fine line between cliche’ and Nicholas Sparks. So, in my attempt to avoid such fate, the only thing I can offer is a secret love story about love. So secret that when my wife reads this, she will know it for the first time.

I’ve written about my health issues and personal shame and failure but writing about love is something I’ve avoided. For me, writing about love is a little embarrassing. A little too revealing.

And plus, how do I write about love in such an authentic yet impenetrable way that it’s not the subject of dissection, comparison and judgment?

Truth is– you can’t.

It’s simple emotional physics (which should’ve totally been a 90’s emo band name).

To love is to want. And to want is to have weakness. Therefore, you can’t open yourself to love without subjecting yourself to dissection, comparison and judgment.

I fell in love with a girl when I was 16.

The first time I saw her standing in the blue painted threshold of the doorway to her biology class I just knew, with an absolute bone-certainty that I would marry her one day.

And 10 years later I did.

Even though that story is absolutely true, I understand you’re skepticism. And I don’t blame you. It seems too easy and yet, at the same time, too impossible. Too Nicholas Sparks.

So I’ll tell you another story that’s more believable. Yet, in some ways, just as fantastical.

Cindy and I are sitting at large round table, the kind guests sit around at weddings. We’re in the back of a Las Vegas hotel ballroom, the kind couples rent for weddings.

Except instead of a DJ, there’s a UCLA professor at the far end of the ballroom. He’s standing on a stage, behind a podium. To his right is a movie screen holding an MRI of a human brain. A brain whose cerebellum is damaged. A cerebellum that looks a lot like mine.

The room is filled with people of all ages. Some people in wheelchairs. Some people clutching canes and walking sticks. The same haunted glow in everyone’s eyes.

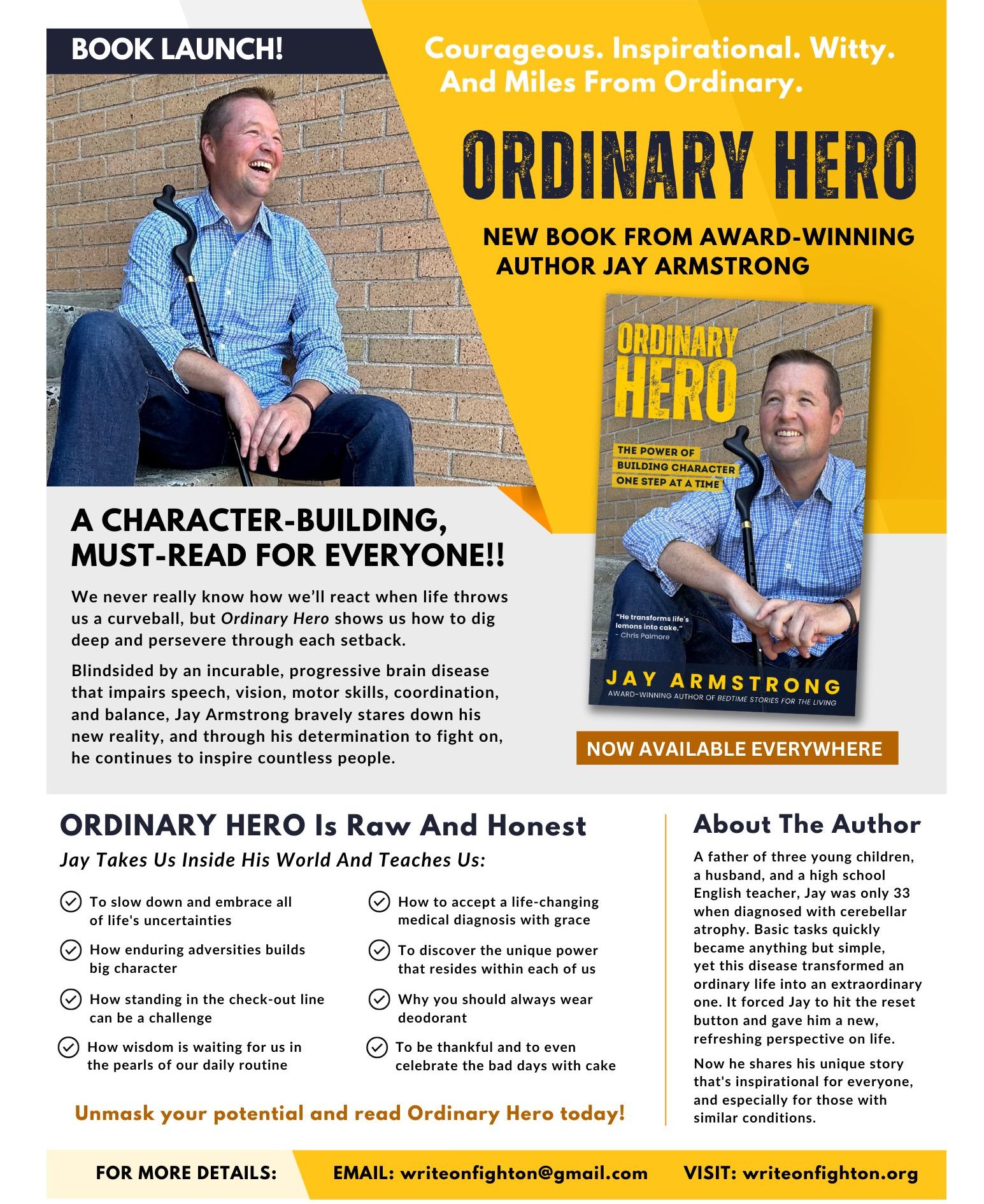

We’re in Las Vegas attending the National Ataxia Federation’s annual conference for patients with neurological disease because seven months earlier I was diagnosed with cerebellar atrophy.

Cindy and I are surrounded by people of all ages stricken with rare neurological diseases. ALS. MS. Huntington’s Disease. Brain tumors.

Some people sit with their spouse. Some sit their parents. Some sit alone.

The UCLA professor is discussing advancements in stem cell research as a way of improving and repairing brain growth.

Cindy is beside me taking notes.

Her hand moves in small yet amazing ways. She is writing down what the professor is saying as fast as he is saying it.

Her penmanship is catholic school perfect. Her notes are well-spaced and organized and her margins are aligned.

It was a secret moment in my history. One I’ve never told Cindy about.

A moment of enormous fear yet as my eyes trace the ink-curls of her words, a small moment of enormous comfort and safety. A moment where love was learned. A moment when I finally realized I was lucky enough to find a woman who cared more for me than I could possibly care for myself.

A moment that gifted me the eventual courage to roll my shoulders and write these sentences–

Let my cerebellum soften to oatmeal. Let my brain cells explode. Let my eyes go blind. Because there’s a girl with green eyes standing in the blue doorway and she’s not moving. And she never will.

And that is what love becomes. After all the romance and celestial promises of the initial courtship, love becomes a lifetime of small moments that add up to make something enormous.

But even that seems Sparksian.

A chronically sick man whose hands are shaking, whose body aches, whose teetering on the edge of self-destruction is sitting beside his wife in a Las Vegas ballroom. They’re high school sweethearts. They have three children together. But seven months ago things suddenly got harder.

And yet she still takes notes.

As the professor speaks and the damaged brain that holds the screen looms like a thundercloud over the room with her free hand, she reaches across the table to hold his hand, to ease him, to feel his pain.